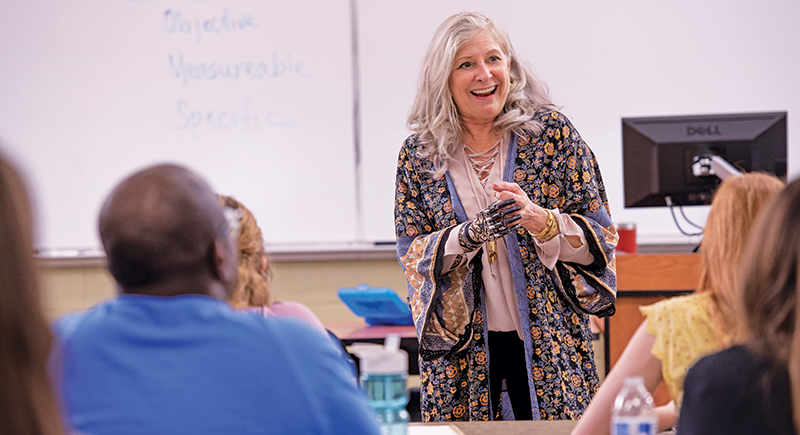

Dr. Debra Latour: Different By Design

Dr. Latour seeks to "make a million differences" as an occupational therapy educator, advocate, and innovator

By Mary McLean Orszulak G’10

One of the first things you notice when you meet

As she speaks and gestures, you realize it’s the clicking of her bracelet worn not on her wrist, but prominently on her prosthetic arm. It’s a visible and audible reminder that

An assistant professor of practice in the second year of the Doctor of Occupational Therapy program at Western New England University,

She’s an educator, therapist, advocate, consultant, inventor, and entrepreneur, who embraces a profound faith and exudes an infectious sense of fun.

Registered in six states, the long-time occupational therapist-turned-academic completed her O.T.D. last spring and is excited to be a part of the innovative three-year Doctor of Occupational Therapy program, one that educates students to be leaders and innovators in the high-growth field of occupational therapy.

Occupational therapists help people participate in the “job of living” through the therapeutic use of everyday activities (occupations). Common interventions include helping children with physical challenges to participate fully in school and social situations, aiding people recovering from

Reflecting the field’s growing demand for therapists with doctoral degrees, Western New England’s program offers a direct path from a bachelor’s to a doctorate with no intermediary master’s degree required. As long as applicants have the proper prerequisites, bachelor’s degrees in many disciplines are viable for enrollment.

“I think I’m inventive because I grew up having my parents rig things up for me all the time. I played guitar. I would have trouble holding on to the pick with my prosthesis, and my dad would conjure up a way for me to do that.” - Dr. Debra Latour

Primed to Persevere

The eldest of six children, she feels fortunate to have grown up in West Springfield, MA, just across the river from the Shriners Hospitals for Children. It was there that her determined young parents brought their infant daughter to be fitted with a prosthetic arm. But they

While her parents were thrilled, young Debi initially rejected her new appendage. It was hot, sticky, and the harness chafed her tender skin. When her parents weren’t looking, the strong-willed toddler routinely threw it in the trash.

“I remember I cried every time my parents put it on me,” says

Watching her father do something so dangerous had a profound impact on Dr. Latour and changed her relationship with the device. She knew it must be something valuable and important. Despite periodic tears, she learned to use it to pull up her own zippers, tie her shoes, and do the occupational tasks learned by other children preparing for school.

"My whole life has been just one divine appointment, not that it hasn’t been without challenges or sorrows or hardships. I wouldn’t say it was a totally charmed life, but I certainly am blessed and have had a great life." - Dr. Debra Latour

A Lasting Impression

A good student,

He made her sit front row and

When her parents realized what was happening, they made arrangements for their daughter to be transferred and also be assigned to a new guidance counselor, one who didn’t share the teacher’s views. Unfortunately, Dr. Latour had to remain until the end of the semester. On her last day, her mother suggested she make a lasting impression.

“I was mortified to do it and didn’t like drawing attention to myself, but I went up to him, told him I had learned a lot in his class, and reached out to shake his hand with my prosthetic arm. He shook my hook and I walked out,” she recalls. “It was one of the hardest things I ever did.”

The Perfect Fit

Seeking to help patients beyond those in her personal care, she created a blog.

Inspired Design

As a young woman,

She offered the patent rights to Shriners, where she worked at the time, because “I wanted to leave something behind with the entity that had given to me,” she says. When the small marketplace for upper limb difference technology didn’t procure a community partner to distribute or manufacture the devices,

Championing “Unlimbited ” Wellness

What drew

Part of the goal of

She’s determined to make that practice history. “If I can protect a generation through preventative strategies and awareness, then maybe I can make a real difference.”